I’ve been studying up to help out on a future John Stossel segment which will likely address the EPA’s overreach in trying to reduce pollution to vanishingly small levels.

Of course, if we could do such a thing at reasonable cost, and there were clear benefits to human health and welfare, then such a goal might make sense. But what was once a noble and achievable goal to clean up most of our air and water pollution has become an end in itself: to keep making things cleaner and cleaner, no matter the cost.

I remember driving through the Gary, Indiana industrial complex in the 1960s. The air pollution was simply unbelievable. You could not escape the stench and smoke; rolling up the car windows did not help.

I also remember the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969. There is no question that the EPA has greatly helped…but we must remember that the EPA was the result of the public’s realization that is was time to start cleaning up some of our messes.

The fundamental problem, though, is that the EPA was given what amounts to limitless power. They do not have to show that their regulations will not do more harm than good to human health and welfare. Now, I will admit they do provide periodic reports on their estimates of costs versus benefits of regulations, but the benefits are often based upon questionable statistical studies which have poor correlations, very little statistical signal, and little cause-and-effect evidence that certain pollutants are actually dangerous to humans.

And the costs of those regulations to the private sector are only the direct costs, because indirect costs to the economy as a whole are so difficult to assess.

Even if some (or even all) pollutants present some risk to human health and welfare, it makes no sense to spend more and more money to reduce that risk to arbitrarily low levels at the expense of more worthy goals.

Economists will tell you that society has unlimited wants but only limited resources, and so we must choose carefully to achieve maximum benefits with minimum cost. It is easy to come up with ideas that will “save lives”; it is not so easy to figure out how many lives your idea will cost. The same is true of government jobs programs, which only create special interest jobs at the expense of more useful (to the consumer) private sector jobs.

The indirect costs to the economy can be the greatest costs, and since we know very well that poverty kills, when we reduce economic prosperity, people — especially poor people — die.

Income is directly proportional to longevity; you cannot keep siphoning off money to chase the impossible dream of pure air and pure water, because those are simply not achievable goals. It makes absolutely no sense to give a government agency unlimited authority to regulate pollution to arbitrarily low levels with no concern over the indirect cost to society.

But that’s what we have with today’s EPA. Several years ago I gave an invited talk at a meeting of CAPCA, the Carolinas Air Pollution Control Association. There was also an EPA representative who spoke, and to everyone’s amazement stated something to the effect that “we can’t stop pushing for cleaner and cleaner air”. Eyebrows were raised because in the real world, such a stated goal ignores physical and economic realities. There is no way to totally avoid pollution, only reduce it.

How far we reduce it is the question, and so far the EPA really does not care how many people they might kill in the process. Or, they are too dumb to understand such basic economic principles.

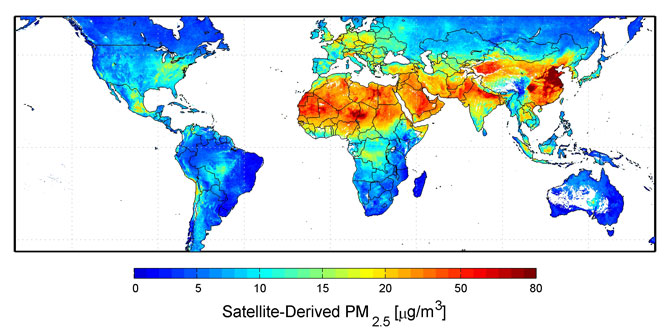

Let’s take the example of fine particulate matter in the air (the so-called PM2.5, particles less than 2.5 microns in size), which the EPA recently decided is unsafe at any level (“no threshold” at which it is safe). Let’s take a look at a satellite estimate of the global distribution of this “pollution”:

You will note that the most “polluted” air occurs where almost no one is around to pollute: in the deserts. This is because wind blowing over bare soil causes dust particles. If you really are worried about fine particulate air pollution, do not go outside on a windy day.

Also note in the above map the blue to cyan areas, which have concentrations below 10 micrograms per cubic meter. Those are levels the World Health Organization has previously deemed safe. The western United States is largely below that level. If one examines the monitoring station data west of Denver, there is no correlation between changes in fine particulate matter pollution and deaths, but the oft-quoted Pope et al analysis of those data lumps all of the U.S. data together and finds a weak statistical relationship between deaths and changes in fine particulate pollution.

The EPA then concludes that NO level of such pollution is safe, even though the data from the western U.S. suggests there is a safe level.

As a scientist who deals in statistics and large datasets on almost a daily basis, I can tell you it is easy to fool yourself with statistical correlations. The risk levels that epidemiologists talk about these days for air pollution are around 5% or 10% increased risk compared to background. This is in the noise level compared to the increased health risk from cigarette smoking, which is more like 1,500%. When statistical signals are that small, one needs to look far and wide for confounding factors, that is, other more important variables you may not have accounted for to the accuracy needed to make any significant conclusion.

Actually establishing a mechanism of disease causation is not required for the EPA to regulate; just weak correlations and a board of “independent” scientific advisers who are themselves supported by the EPA.

Of course, when Congress makes any attempt to rein in the EPA, there are screams that decades of air pollution control progress is being “rolled back”. Bulls&!t. The new pollution regulations now being considered have reached the point of diminishing returns and greatly increased cost.

This week I was with about 250 representatives of various companies involved in different aspects of growing America’s (and a good part of the world’s) food supply. The most common complaint is the overreach of government regulation, which is increasing costs for everyone. The extra costs have been somewhat shielded from the consumer by industry, but they told me that sharply increasing food prices are now inevitable, in fact they are already showing up in grocery stores.

And I haven’t even mentioned carbon dioxide regulations. Even if we could substantially reduce U.S. CO2 emissions in the next 20 years, which barring some new technology is virtually impossible, the resulting (theoretically-computed) impact on U.S or global temperatures would be unmeasurable….hundredths of a degree C at best.

The cost in terms of human suffering, however, will be immense.

It is time for the public to demand that Congress limit the EPA’s authority. The EPA operates outside of real world constraints, and is itself an increasing threat to human health and welfare — the very things that the EPA was created to protect.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog