We hear that a new El Nino forming in the Pacific Ocean is likely to push global-average temperatures to new record highs in 2023.

Setting aside the fact that we have no idea if current temperatures are warmer than during the Medieval Warm Period of ~1,000 years ago, I have to ask…

So what?

Doing something about global warming depends a lot on how much we are asked to pay to fix it. If it was cheap and practical, we would have already transitioned to renewable energy sources.

It also depends upon just how much global warming we have experienced, and whether it is enough to be concerned with. For the global oceans, the climate models enlisted to scare us in a steady stream of alarmist news reports over-predict ocean warming by a factor of 2. In America’s heartland during the summer, the discrepancy is a factor of 6(!). So, clearly, public concern is being inflated by factually incorrect information.

What Temperature do Americans Choose?

When it comes to life in these United States, roughly 50% of U.S. residents have at least a moderate worry about climate change and global warming. As mentioned above, I believe this is largely due to their response to what is reported by the news media, which is routinely exaggerated.

An interesting question that the late Dr. Pat Michaels asked about 25 years ago is, what temperature do Americans choose to live with? We have a large country with a wide range of climates, from frigid winters to tropical year-round, so there is considerable choice of what climate we decide to live in.

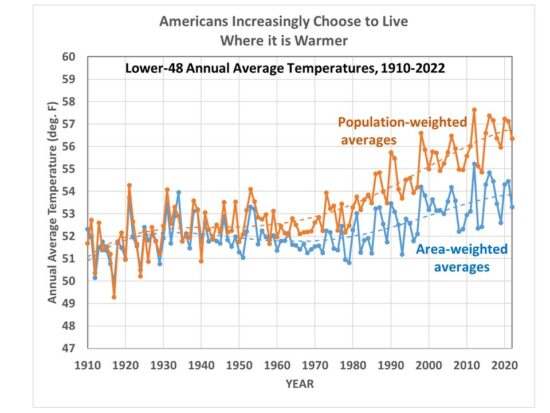

Dr. Michaels pointed out (most recently in 2013) that over the years, Americans tend to migrate to warmer climates. Some of us might claim to be concerned about global warming, but we increasingly choose to live where it’s warmer. I’ve updated those calculations to 2022, and the results are the same:

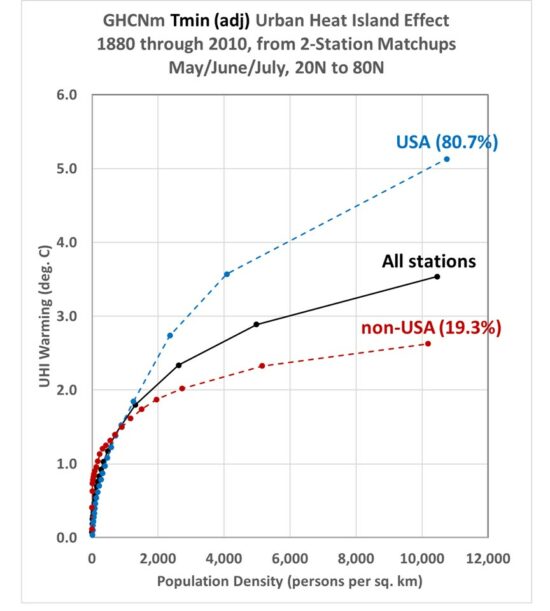

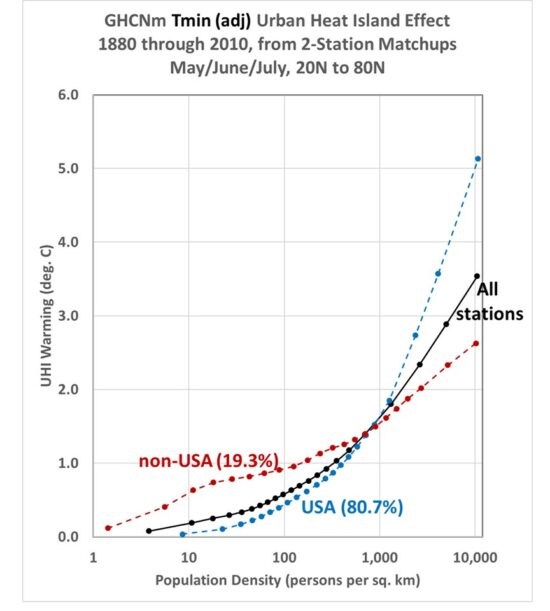

The blue curve is the usual area-averaged temperatures for the Lower 48, while the orange curve is the state population-weighted average. While the area average temperatures have warmed modestly over the last century, the temperatures where people choose to live have increased by twice that amount. (The possibility that Urban Heat Island effects have spuriously warmed these NOAA-reported temperatures is part of a research project we have been involved in).

Some might claim that the migration to states with warmer temperatures has more to do with economic opportunity than with temperature. But who creates economic opportunity? People. And where do people choose to live? Where the weather is warmer.

There’s a reason why people are flocking to Texas and Florida, and not to the Dakotas or Maine. Ultimately, it’s due to the climate. So, while some of us like to think we are Saving the Earth by buying a Tesla, our migration habits are telling a different story.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog